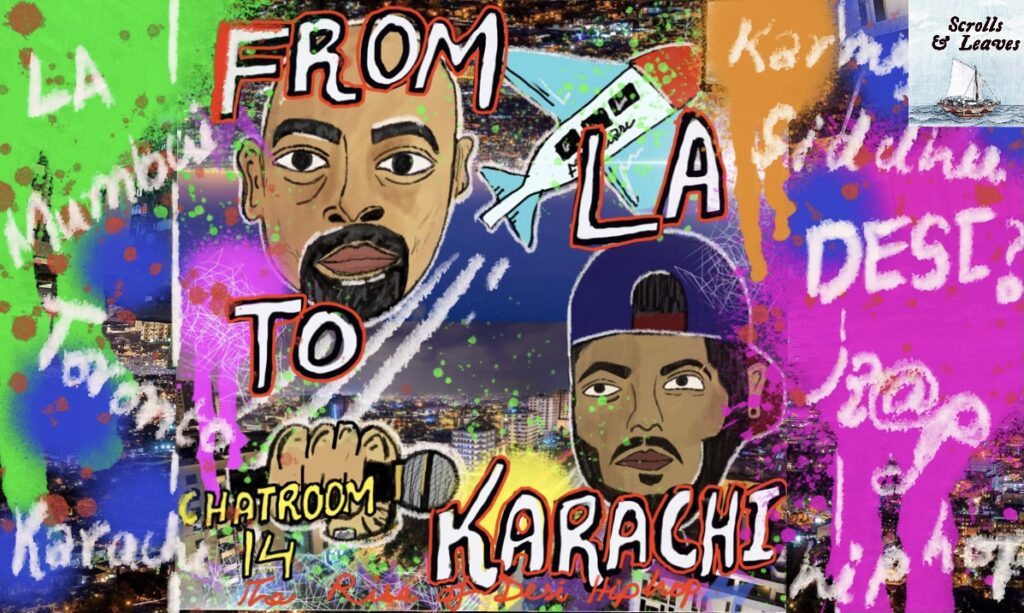

The rise of Desi Hip Hop is the result of the South Asian diaspora looking for ways to express their identity. It’s spread across the world. Listen to Chatroom 14 here.

Art by Iman Iftikhar

Gayathri Vaidyanathan: This is Chatroom 14, your bonus episode of Scrolls & Leaves. I’m Gayathri Vaidyanathan. In this episode, you’ll be traveling with Hip Hop around the world, from LA to the streets of Karachi. This episode is produced by students at Yale University who are interning with us.

GV: And, a small request — If you’re liking what you hear, why not consider donating? Details on our website, scrollsandleaves.com/support.

Adnan Baloch: Mera naam Adnan Baloch hai aur main Malir kay aik rural area se belong karta hun.

Waleed Iftikhar: My name is Adnan Baloch [ADh-Naan Ba-LOKh] and I am from a rural area in Malir.

Iman Iftikhar: The song you heard is by Adnan is a 24-year old Pakistani rapper. And unlike most other rappers who hail from a neighborhood in Karachi called Lyari, which is also known as Karachi’s ghetto, Adnan is — from a quiet, sleepy town surrounded by farmlands to the north of the city.

AB: Main Balochi main rap karta hun takay main apnay culture ko dikha sakun. Agar meray ird gard koi masla hota hai to main us main rap karta hun. Rap to wahi hai jo social issues ko highlight kare. Jesay maira urdu main aik track araha hai, drugs kay baray main, manshiyaat. Aur main dikhana chahta hun kay sab is maslay ko note karein. Ye sab ka problem hai.

WI: I rap in Balochi to highlight my culture. If there is a social issue plaguing the community, I rap about that. This is what rap is… it highlights problems. For example, I have a new track in Urdu about drugs. I want people to pay attention to this, the boom in drug usage is a problem that affects everyone.

II: Rap is a musical genre that is part of hip hop. Hip Hop, if you don’t know, started as a street culture and includes rapping, DJing, breakdancing and graffiti. In the early 1970s in the South Bronx in New York City, people were facing tough living conditions and harsh policing tactics. In 1973, 16-year old Clive Campbell threw a dance party in the rec room of the apartment building he was living in, and he used two turntables to elongate the breaks in funk records… by artists like James Brown, and a new musical style was born. Campbell was soon known around the Bronx as DJ Kool Herc, and together with Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash, he’s seen as a pioneer of hip hop.

Alexa Stanger: Young people would hook up their speakers to stadium lights and play records on turntables. They’d scratch and sample. They’d dance and reclaim public spaces that were being increasingly policed and restricted.

II: So, how did this music get from the Bronx to the streets of Karachi 8000 miles away? Find out in today’s chatroom.. “From LA to Karachi, The Rise of Desi Hip Hop.” I’m Iman Iftikhar.

AS: And I’m Alexa Stanger. AS: Today, we’ll be speaking to Adnan and to a pioneer of Desi Hip Hop. Stay with us till the end to hear some live rap from Adnan. This episode is based on the book, Hip Hop Desis: South Asian Americans, Blackness, and a Global Race Consciousness, by Nitasha Sharma at Northwestern University in Chicago. The music featured in this episode is from Adnan Baloch and Rukus Avenue.

II: So what gives Hip Hop a Desi flavor?

Sammy Chand: I think it’s this interpretation of the culture, giving your own spin on it from either a story perspective, or giving it something unique for a music perspective is really what I think we have to give to this hip hop genre. I’m hearing music nowadays, that spiritual hip hop ! That incorporates, you know, principles of yoga and meditation into hip hop, you may say that this could be somewhat of a secondary or even an advanced interpretation of Indian culture making its way into it.

II: That’s Sammy Chand — he’s one of the pioneers of Desi Hip Hop… a record producer, rapper and founder of Rukus Avenue, a Los-Angeles based independent label that supports emerging Desi artists. The mission of Rukus avenue is to create music that’s a mix of Eastern and Western Cultures. It represents artists like Siva Kaneswaran, Ruby Ibarra and Satinder Saartaj.

AS: When people think of Desi Hip Hop, at least some will think of Sammy.

SC: When I started doing this, I was probably the first Indian kid, maybe around the world rapping like this.

AS: In the late 1990s, Sammy Chand was in highschool and he and his Desi friends were all listening to Hip Hop. II: So they wondered… What can we do with this sound? How can we take this medium, this music, and combine it with our experiences to make it our own?

II: In his 20s, Sammy and three of his South Asian friends formed the first desi rap group in America. It’s called Karmacy.

SC: At the time, when we were rapping, especially from the South Asian community perspective, there were very few of us doing it nationwide. In fact, I can probably count all of us on one hand at that moment. Although, you know, at the time, there wasn’t a scene for it, we were each of us doing things in our own individual space, particularly amongst the mainstream, hip hop community. And in doing so, we felt that we were not articulating a voice of not only an immigrant experience, or even a second generational experience. But we weren’t really talking about our own community condition, what was going on, the politics, the news, the information, the perspectives. And so the four of us at the time when we started doing our thing as a group, it was more so because there was a void. There was no voice in this space, and we wanted to go kind of, you know, adopt it.

II: Nitasha Sharma writes that Asian Americans in hip hop have been mostly invisible. This is sorta like how Desi folks are seen — or rather, I should say… unseen… in America…they’re there but invisible, the so-called model minority. They don’t really fit into the Black-White conceptions of race.

II: And that’s why South Asian youngsters are taking to rap, because the genre gives voice to the oppressed and the silent, it allows for self-representation.

AS: Sammy’s career took off in California, which has the largest number of Indians in the US.

SC: California, being a home to so many of us South Asians here, that definitely lent itself to an advantage. There was a sense of California providing a little bit more of a whether it was a socio-economic, but also a political environment for four Indian kids to go call themselves a group and go do shows, and not be looked at too strangely. Although we were looked at strangely, but not too strangely. Whereas in some other states maybe around the country that may not have been an easy thing to accomplish, from a cultural perspective, from a racism perspective. We were four Indian kids rapping. And that in itself was quite a visual. And I don’t think a lot of people were open to seeing that, unless they were in places where there was already some sort of cultural explanation or context for somebody to say, ‘you know what? I’ll check out these four Indian kids rapping and see what they have to say!’

II: Karmacy helped pave the way for South Asians to use rap to claim their space to craft and reshape their identity in America.

AS: Sammy and his group often sampled a bhangra [BhunG- Rra] or dhol [[DhOll] beat and music from the subcontinent. Listen to their beats here in this song called Blood Brothers.

SC: Our most popular song was a song called Blood Brothers. It spoke of the immigrant struggle in three verses that were articulating everything from what drives a family member to leave India to migrate, to everything from assimilation and the struggle of assimilation to subsequently, perspective on the entire process, maybe a generational perspective of what that move meant to them.

SC: Here in the United States, at the time, when a lot of the immigration Hot Topic stuff was popping up, especially in the early 2000s here, it was really looked at as a song that really spoke of the South Asian struggle and South Asian story. And I think it helped a lot of people understand not only why their ancestors made the move here, but also helped them understand that the assimilation process was not easy.

AS: From California, the music spread across the world. From Toronto, across London, to the streets of Mumbai and Karachi. Today, Desi rap is everywhere.

SC: It’s been interesting to see the different reflections of hip hop culture. Sidhu Moose Wala from Toronto uses Punjabi music. He’s from this really deep-rooted Punjabi community in the suburbs of Toronto, right? And then you have Divine in Mumbai, who’s got his whole kind of following coming up from the gully rap scene. As far as how we’ve seen, you know, the adoption of community and culture into this into the sound, we have really found that you’re going to see different kinds of takes on it. In London, you heard this different sound that was built out of this grime sound that was coming out. And Toronto, you heard a little bit of Punjabi Bhangra scene because that’s what’s there. I think you’re going to continue to see these hubs of people that were immigrants that moved into the spaces, adopted the communities and got to learn and are directly reflecting to you, who they’ve become in their music.

SC: London has its thing on it. It’s different from what we hear in LA. Same with Toronto, same of Vancouver, same with Mumbai, and of course, what you’re hearing out of Punjab or some of these other places, and dare I say even the Far East and stuff… you are hearing the reflections of this stuff coming together, of what they adopted, what they took on what aspects of the languages that we brought on board. This is interesting. I think that the ethnomusicology of hip hop and South Asian hip hop, and specifically how Indians have moved to these different hubs, as they’ve adjusted to those communities and then what they decide to put on tape is really, really cool to watch. And it’s cool to see the evolution of it…really is.

II: Sammy says that these days, many hip hop artists are going to South Asia, and returning with unique sounds that are really pushing the boundaries of Desi hip hop.

SC: You’re seeing this really cool thing happening in our South Asian hip hop space. And that is what I consider the return path. You’re seeing a lot of the artists now that are coming back from India, that have really embraced the hip hop culture, whether they’re rapping in English or even in Indian languages, whatever, Hindi, whatever, Punjabi, whatever. They’re really kind of going back and embracing the art form and taking that to another level.

II: So, this is Adnan again… we’re back on the subcontinent with him in Karachi. In 2012, he was hanging out at a shop in Karachi’s Saddar Bazaar … and, you know, it had this dinky small TV like these shops do.. .and it was playing an interview with a rapper who looked just like him! It was Bohemia, a Pakistani-American rapper and a friend of Sammy’s. And that’s when Adnan caught the bug… he’s been rapping ever since.

AB: Mainay aik interview dekha tha Bohemia ka takreeban bohat pehlay. Bohemia wo artist hai jo hain pakistani but wo out of country hain America main. Rap wo laiy thay Pakistan or india main. Unka aik interview tha aur wo bata rahay thay kay meray aik aisa haal tha ka main music banaraha tha aur meray paas bohat maslay thay, meray paas khanay ko kuch nahin tha, aur main chewing gum khata tha. Aur unhay nay phir rap karna shoro kiya America main aur represent kiya humain apni zubaan main ga kar. Aur mainay unhay suna to mujhay bohat acha laga. Unho nay ye dekhaya kay rap hai aur yahan bhi hai or log suntay hain.

WI: Bohemia brought rap to Pakistan and India. In this interview, he was saying that when he first started making music, he had a lot of problems. He had no food, and he chewed gum for entire days. That’s when he started rapping and made it in America. He represented us, our community, in our language. When I heard him talking, I knew this was it! He showed that rap belonged also in South Asia, we are also rappers.

II: Adnan is still very much an emerging artist. He releases under his own Urdu Rap label. He drops his songs on YouTube, and has a significant social media presence… truly an artist of our times…

AB: Har cheez ko time deraha hun, passion hai. Isi liyay karta hun kay main rap na karta to patin nahin kahan hota. Main music na karta to pata nahin kya karta. Allah maaf karay, drugs main chala jata. Bas mera passion hai jo mujhay lejara hai.

WI: I give time to everything. I rap because if I didn’t, I don’t know where I would be. If I didn’t make music, I don’t know where I’d be. God help me, I could have gone into drugs. It’s my passion for rapping that has brought me this far.

II: Adnan, can you take us out by rapping a little?

<Adnan’s rap>

GV: You were listening to Iman Iftikhar, Alexa Stanger, Adnan Baloch and Sammy Chand on Chatroom 14. Adnan’s translation was voiced by Waleed Iftikhar. The sound in this episode was handled by Sasha Semina. For more information and other episodes, visit scrollsandleaves.com. Follow us on Twitter at scrollsleaves, or on Instagram at scrolls and leaves, or like us on Facebook. We’ll be back in a couple of weeks with another chatroom, this time we’ll tell you about Tuvan throat singing. Stay tuned!