The link between pandemics and borders can be traced back to a 19th century outbreak of cholera in Jessore, Bengal in 1817. Listen to the episode here.

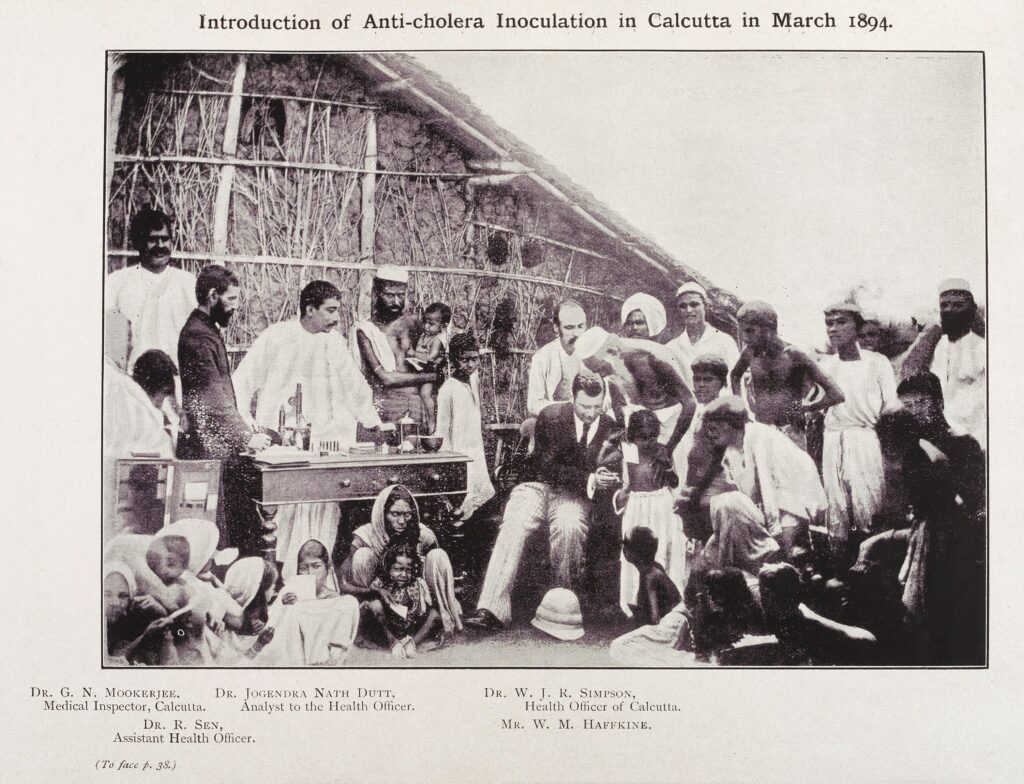

Haffkine delivering cholera inoculations. Credit: Wellcome Collection

Mary-Rose: Please wear your headphones if you’d like to hear this in 3D.

Gayathri: This is Chapter 1 – Nightmare at Frankfurt Airport.

Gayathri: on April 22nd this year, Canada banned direct flights from India because of the coronavirus pandemic… On May 1st, India recorded a whopping 400,000 new cases in a single day. The second wave was fueled by a new variant called Delta. Those were insanely difficult times. But the second wave did decline, and yet, Canada continued to ban flights, and mostly only from India. Here’s a clip from August, from the Indian news channel WION.

Anchor: “Today Canada has decided to extend the flight ban from India. Why? Virus concerns, they say. But what about the US where cases are mounting? No restrictions there, Americans can travel to Canada, all they need is proof of vaccination. But no such option has been given to Indians. Again, why?”

Mary-Rose: The ban continued for five months. So Indians had to find some creative routes to get to Canada. One of them was Aneerudh, a student from Bangalore who lived through a version of the movie Terminal to get to his university. We won’t share his last name for privacy reasons. He did his first year of college remotely, staying up all night for 2 semesters to attend classes. He’d had enough of it and was determined to get on campus for the new semester. And this was his last shot, for this year at least. Here’s his story.

Aneerudh: I’m currently in my second year studying Bachelor of Business Studies. I did my schooling in Bangalore. I’m 19 years old. I’m a very extroverted kind of person. I like playing a lot of sports. I surely don’t like studying. I like making friends and always doing something adventurous. So , me being me, I want to go as far as possible to experience the world and try to make it on my own.

Gayathri: So, Aneerudh got into the university of Alberta, got his visa in January and booked his flight for April 25th. But then, Canada banned all direct flights 3 days before that. And not just that — they refused to accept any RT-PCR tests from India. So, the only way Indians could get to Canada was to stop in a third country, do a test there, and then go on to Canada.

Mary-Rose: Now, this is a drastic move because of the number of people it affects – more than a million … Indians are the largest immigrant community in Canada.

Aneerudh: so that was pretty disappointing.

Mary-Rose: So Indians began finding alternate routes to get to Canada.

Aneerudh: So there were a bunch of countries. So I think the first one to open was Cairo, Egypt. So you take a flight from India to Egypt, you stay in Egypt for three days. And get your RT PCR done there. And from Egypt, you fly to Toronto.

There was Mexico, because Mexico, you have an on arrival visa option. And then there is Delhi, Doha, Serbia, you can get your RT PCR done in Serbia, and then from Serbia, to Frankfurt…

So the route I came in is via Muscat. I’m extremely lucky, because mine was the last flight, which actually came through Moscow. And Ethiopia was having that elections or something, and there was a lot of violence. So that was cancelled. And there was a new variant concern in Serbia. So that got shut down three days back.

Gayathri: As Aneerudh spoke, I was reminded of the Mediterranean refugee crisis and the routes that the refugees, asylum seekers and migrants engineered to get into Europe. These routes were always flickering on and off as well…

Now, a lot of these routes that Aneerudh mentioned cropped up after July, when cases declined remember? So now, in case you are thinking this is okay, covid is a unique circumstance — let me ask you this. Is Covid from India special somehow? Because by June, the Delta variant had spread to dozens of other countries where Canadians were allowing travel from. Or is it that Indians are more likely to cheat on their RT-PCR tests? And if so, isn’t this stereotyping?

Mary-Rose: So an interesting point here… Indians and most people from the poor world need to do a battery of medical tests to go to Canada… a blood test, urine, eyesight, scan of your lungs to check for TB.. people from rich countries don’t have to do this.

Aneerudh gets his medical tests on May 23rd. And on June 16…

Aneerudh: I flew from Bangalore to Delhi, and from Delhi to Muscat, I got my COVID test done in Muscat.

Mary-Rose: The layover in Oman was 16 hours!!!…

Aneerudh: I got a negative result. And I flew from Muscat to Frankfurt.

Mary-Rose: In Germany, he gets in line to board the Air Canada flight to Toronto…

Aneerudh: I still remember just standing there and everybody’s passport scans, there’s no sound and my passport, it goes beep beep. I was like, Oh, I think he’s not scanned it properly, or the machine is not working or something like that. He scans it again, and it’s beep beep again. At the bottom of the visa, there is a is a barcode or a couple of numbers. So when they scan that, on their machine, it said invalid. No, you can’t get on the flight. If your visa is not valid, you’re not you’re not going into Canada. As simple as that. I was I was I was in shock. I took a minute or two to process the entire thing. The officer was very rude to me. And he said no, you just you can’t fly, I’m sorry, just move out of the line. Don’t keep my line held.mI knew that the problem was with my medicals. they hadn’t updated on their system yet. That’s basically means I was stranded in Frankfurt Airport.

Gayathri: Due to COVID, Canada was not on the ball in processing visa applications. While immigration at any time is a hassle, it has become a special treat during the pandemic!

Gayathri: Aneerudh and his family scramble. If he goes back to India, it’s unlikely he can make it to Canada for the August semester. It’s a lot of money and a logistical nightmare.

So they hire a lawyer in Toronto, call the university and finally get an email address for Canadian immigration services, and send them a desperate message. It’s been two days since his journey began.

Mary-Rose: And Aneerudh is hanging out in Frankfurt airport –he’s hungry, tired, lugging bags from one terminal to another. The night passes.. chances look slim. So his parents book him on a return flight to Bangalore. He goes to the gate…

Aneerudh; I was just putting my head down. And I get a call from Amama. And she said that, just check your email immediately. So I opened it. And I just saw one sentence, which said, We’re sorry to have overlooked your medical, which was retaken on 23rd. Your visa is now updated and valid, you may enter Canada. So I at that point. I was like, oh, wow, okay, what is this? It was like a movie.

Gayathri: So, he books the next flight to Toronto that’ll leave 24 hours later.

Aneerudh: On the 19th, I boarded that flight. I was so happy when she scanned my passport and there was no beep and I flew finally from Frankfurt to Toronto.

Gayathri: He gets a 3rd!! Covid test after landing in Toronto, and then goes to a government-appointed hotel for 3 days of mandatory quarantine. This costs more than a 1000 dollars.

Aneerudh: When I saw the room, I was like, Ah, that’s the bed. I think I slept for like 13 or 14 hours straight and my body was like broken.

Gayathri: Then, a last flight to his university town and home! Overall, Aneerudh spent about a week getting to his destination.

Mary-Rose: So, we told you this story because… well, it’s so unfair that people from one country are targeted. Remember, India’s second covid wave rapidly declined by the end of June. As of late September, it still has about 80 cases per million people living in cities. Which is lower than the rate in the US. But Americans can travel in with a vaccine certificate and a PCR test.

Gayathri: The Canadian measures are just a harsher shade of discrimination that almost all nations have imposed during Covid.

Mary-Rose: Border control is an important public health measure for sure. But did we ever imagine we would sacrifice so much civil liberty in so short a time? That we’d be okay with our governments tracking us, restricting our movement? We now have to prove we are not carriers of disease.

Gayathri: These aren’t abstract intellectual questions we’re posing… we’re talking about people’s lives. Who gets to cross a border, board a plane, go to a restaurant… and who doesn’t? Who is undesired? What race are they? What class? What caste? What nationality?

Mary-Rose: And how did we get here, to this moment? Why these responses to a pandemic? This is Episode 4 – Pandemics & Borders

Intro — Pandemics and Borders

Gayathri: Welcome to Scrolls and Leaves, a world history podcast featuring stories from the margins. We’re in season 1, Trade Winds, set in the Indian Ocean World. I’m Gayathri Vaidyanathan

Mary-Rose: And I’m Mary Rose Abraham. We have a small request… we’re an independent podcast, and donations from listeners like you will ensure we are compensated for our time. Please visit scrollsandleaves.com/support for details.

Gayathri: In this episode, we’ll tell you about the origins of the world’s responses to Covid19. It began with a pandemic 200 years ago– it was the first truly global outbreak since the plague of the 14th century, which you may know as the Black Death And Pratik Chakrabarti, a historian of medicine at the University of Manchester in the UK says this disease changed everything– our notions of

Pratik Chakrabarti: …of trade, commerce, disease. Cholera you can almost read as a case study of modern pandemics, you know, it’s a useful mirror to understand all subsequent modern pandemics by

Gayathri: The world changed when cholera broke out in Bengal in 1817.

Mary-Rose: Chapter 2 – Pandemic

Mary-Rose: Before the 1800s, there aren’t many mentions of pandemics in Indian history books. There was smallpox, occasional bouts of mysterious fevers… but no mentions of big epidemics. That is because disease took time to spread

Gayathri: It had to sail over oceans, clamber through jungles… trek across deserts….it travelled at the speed of caravans. Stopped for tea at remote outposts. And often, the weather would change, or the local scenery would go from valley to mountain, and it’d die out there — all alone. It usually took ages – decades, even centuries – to get around the world. So, things are plodding along until…

Mary-Rose: The 19th century. Steamships replace sailing ships, so people are able to get around quicker. Europeans colonize large parts of Asia and Africa — they go from traders to rulers of the subcontinent. Here’s David Arnold, a renowned historian of South Asian medicine at Warwick University in the UK. …

David Arnold: India was particularly important, particularly with the coming of colonialism from the very end of the 15th century onwards… It introduces a new population of Europeans who had their own diseases or their own disease susceptibility. It enhances links with Eastern and Southern Africa. It increases contact with Southeast Asia through to China.

Gayathri: These were great conditions for a pandemic. Let’s go back to 1817, to a town in Bengal in West India…This is non-fiction, embellished very lightly for colour

Sumit Kumar: It’s been raining since January. The heat has been churning up the swamps, and the vapour hangs heavy. Robert Tytler , a British surgeon in Jessore has been expecting an outbreak.

Still, he is unprepared for 19th August. A native doctor, or vaidya, knocks on his door. Something’s wrong in the bazaar, the vaidya says.

The bazaar is the Indian part of town. It’s 2-miles long, next to the Bhairab River. Across the river is a swamp. It’s so congested — people are selling food from their doorways and Tytler scrunches up his nose in disgust. The huts are narrow as can be…dark and damp inside.

The vaidya takes Tytler to a hut. A man is lying on a mat on the ground. He is middle-aged. His friends are pouring water into his mouth. Tytler gets closer and sees his face is pale, his forehead beaded with sweat. His eyelids are half closed, and Tytler pulls them up and sees lifeless eyes. His body feels frigid. His pulse is weak.

He was fine yesterday, the vaidya says. Then, during the night, he collapsed in pain. He had diarrhea, vomiting — he kept begging for water.

Tytler is shaken. This seems like cholera.

The next day, the man dies. Within 2 days, another 17 people die in the bazaar.

That year in Calcutta, funeral pyres burn continuously at the ghats leading from Chitpore Road to the Hooghly River. When there’s no more fuel for cremation, bodies are thrown into the river. And in time, there are so many floating corpses that they entangle with the shipping cables. The stench is unbearable, and the magistrates pay Muslim men to clear the bodies.

Mary-Rose: Cholera is unpredictable. Sometimes it claims an entire village, and spares the next one. It disappears, and reappears months later… The only sure thing is that death, when it comes, is swift and painful.

Gayathri: From Jessore, it marches on with British troops. It marches across the subcontinent. To Jaffna in 1818. It hops on the frigate Topaz and sails to Penang. Singapore.

Mary-Rose: Russia in 1823. Persia and Turkey in 1828. Across the Baltic Sea into England and Ireland in 1831. The Americas in 1833.

Gayathri: Six waves of cholera shake the world by the end of the 19th century. Tens of millions of people die globally, at least 10 million in India alone.

Mary-Rose: Chapter 3 – Race

Mary-Rose: People don’t know that cholera is transmitted by dirty water. They first think it’s caused by toxic air and the soils of India emitting these noxious fumes of cholera! So, Europeans name the disease Asiatic cholera or Indian cholera. And that is a problem.

Gayathri: Why? I mean we just said cholera began in Jessore right?

Mary-Rose: Well…for one, British troops were actually the main carriers of the disease around the world at the start. But that was conveniently forgotten. And of course, it’s racist to label a disease by its place of origin.

Projit Mukerji: I often joke with my students that it’s, I feel kinship with cholera, because it’s the most successful South Asian immigrant .

Gayathri: That’s Projit Mukherji, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He doesn’t like it when people say cholera is from India

Projit: there’s a lot of problem with that narrative…

Gayathri: Some Experts claim cholera is from Bengal because there is an old Hindu Goddess named Ola Devi that people prayed to for protection… or… they point to early mentions in ancient…

Projit: Ayurvedic texts

Mary-Rose: Sounds like rather flimsy evidence…

Gayathri: Exactly. Projit says the cholera goddess is actually a 19th century creation… And the Ayurveda texts — they only mention symptoms – diarrhea, fatigue, dehydration…

Mary-Rose:…Those can fit many diseases!

Projit: What is more important is to think of why is there even this pressure to try and find a point zero and to call it Asiatic cholera, say it came from there. And that was very much to do with a lot of 19th century racism. And in fact, like, if you look at the racism, it’s not always to do with South Asia. If you look at cholera globally and cholera, in many ways is the quintessential global disease because it starts off at a period when global travel and contact has been intensified and speeded up so it spreads very quickly it appears global, but in every place you see it and across the world, it often gets associated with other communities…

Mary-Rose: We’re across the ocean on the tiny island that ruled the world. In London ..The poor live in slums with open sewers. People even use water from there. It’s 1853….There’s been a cholera outbreak and a 40-year old physician named John Snow is doing some fine detective work. He looks up the addresses of cholera victims and notes that they all lived near a water pump on Broad Street in Soho. And when he gets that water tested, he finds it’s contaminated. It’s the first hint that cholera is caused by dirty water and not miasmas.

Mary-Rose: The idea takes a while to catch on. And once it does, people realize that they have to improve and protect their water supplies…

Mary-Rose: From the 1850s onwards, Europeans invest heavily in the infrastructure of Paris, London, New York…they install piped water and sanitation. And they protect it carefully .

Gayathri: But back in India, the British colonizers make few improvements. In the 1850s, the British Raj, which is the British government in India, imposes high taxes. The economic system collapses, and there are massive famines. Starving farmers and labourers migrate to slums in cities.. they are eating very little and dying early… in fact, India’s death rate is twice that of Britain at that time.

Gayathri: So, the British officials in India fear they will catch diseases from Indians. And they draw borders around themselves. They set up “white towns” where, you know, white people live.

Mary-Rose: white towns? Seriously?

Gayathri: yes! And the Indian quarters were called black towns. Here’s Tarangini Sriraman, a historian from Azim Premji University in Bangalore..

Tarangini Sriraman: “It was important to ensure that there was not too much of coming and going off of Indians into the white town… except of course, to ensure that there’s enough of menial services that are made available.

Mary-Rose: And the next thing they did is improve the water and sanitation in the white towns. Here’s Pratik Chakrabarti

Pratik Chakrabarti: I work at the Centre for History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester, UK

Mary-Rose: he says the British built a dual water system — one for Europeans and another for Indians.

Pratik: So what they did is the river water is filtered and passed onto certain households. And there is another water supply, which is unfiltered water so that unfiltered water went to the Black City.So the citizens in living in the Black City collected water from the local ponds, the same water that is used for multiple purposes. I’m not going into the details of it but you can imagine what I mean by that.

Gayathri: That’s crazy… does it work to stop cholera?

Mary-Rose: yeah, in the white towns! but not anywhere else…

Gayathri: And what do the British say to justify their actions?

Mary-Rose: well… the British officials think that India’s cholera is somehow unique. They simply say that cholera belongs to Indians — it’s caused by.. in air quotes… “local influences” so there’s no point fixing something that’s broken beyond repair…

Mary-Rose: Chapter 4 — Surveillance

Mary-Rose: We’re in 1865. Europe is reeling from the 4th cholera pandemic. This one began in the Ganges delta, hitched a ride on Hajj pilgrims traveling from India to Mecca. And from there to Egypt, and Europe. People are dying by the hundreds of thousands.

Mary-Rose: France isn’t very happy with the situation, so it organizes a massive scientific conference on sanitation. It’s the 3rd International Sanitary Conference. It’s held in Constantinople — modern day Istanbul – in 1866. And Western scientists and diplomats from 18 nations attend.

Mary-Rose: The tone is pretty racist. Many times, they compare themselves to the Roman Empire and Christian crusaders, out to civilize and clean up the East.

Mary-Rose: The conference is a marathon. It goes on for 7 months and 13 days! 44 sessions. And one of the committees discusses the Indian problem.

Gayathri: Oh, what’s that?

Mary-Rose: Well, here’s how the Italian delegate put it: “We have to stop that cursed traveller who lives in India, everyone knows it, from taking his trips; at least we have to stop its progress as closely as possible to its departure point.”

Gayathri: He’s talking about the Hajj pilgrims going to Mecca?

Mary-Rose: Yes. The committee declares India’s pilgrims are the cause of cholera epidemics and they should be monitored. Only the ones who can prove they don’t have disease should be allowed near Europe.

Projit: …So pilgrimages become a major site where the state really starts intervening in unprecedented ways to control mobility. And so there are all kinds of ways in which we actually see in India throughout the 1800s, what the world is going to see later …of this gradual kind of development of new powers of state intervention which put the interest of stopping infection above and beyond any kind of respect for civil liberties.

Gayathri: A year after the conference, the French are still peeved and keep pushing the Brits to control their colony… and the British officials finally takes some action..

Mary-Rose: About time!

Gayathri: No – it doesn’t fix water or anything important. Rather, they begin surveillance of Indian pilgrims to control their movement. Here’s a story based on research by historian Katherine Prior.

Sumit Kumar: It’s 1867, one year after the third sanitation conference. HD Robertson, a British official, is preparing for the Kumbh Mela in Hardwar. The spot is on the Ganges, where it exits the Himalayan foothills. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims are expected in April. They will bathe in the river to rid themselves of bad karma.

Robertson meticulously plans the sanitation. He charges a tax on the pilgrims and traders to pay for upgrades. He doesn’t want a cholera outbreak on his watch. His men dig trench latrines near the main camp that everyone must use. It stinks. There is little privacy. And they patrol the jungles and the riverbank to drive out anyone trying to relieve themselves there.

Some women do not go to the toilet for 2 or 3 days.

Despite the measures, 19 people die of cholera. And as the pilgrims head back home, they leave a trail of disease. The Brits are frantic, they stop pilgrims at rail stations and bridges to examine them for symptoms. The pilgrims are made to bypass larger towns; some have to walk miles in the heat, through heavy sand, without food or water. Some die from the journey.

Officers also quarantine some pilgrims for 2 to 5 days before they can enter their hometowns. If a person dies from cholera, they quickly burn his body and possessions. about half of die… Around 125,000 people die.

It’s the first outbreak of this size at Hardwar. The pilgrims blame the interference of the Brits. They are not wrong.

An inquiry finds that – Robertson’s men buried the excrement from the trench latrines in the porous riverbank right next to the Ganges. The ground must have been impregnated with sewage. It must have contaminated the Ganges, where people were bathing.

Gayathri: That’s one account of the use of policing for public health reasons. The British Raj defines borders and enforces them… borders between pilgrims and the others, towns and outside towns.. between the clean and unclean. Pilgrims became objects of surveillance.

Projit: all the stuff that we think are like what modern states do is actually developed in places like India because these are like the laboratories of modernity. Because in Europe there are other concerns about things like civil liberties, which they don’t care about in the colonies, they can push people around no end.

Mary-Rose: Here’s another account of surveillance– this time of Muslim pilgrims going to Mecca. Based on work by historian Saurabh Mishra, here’s a story of what a Muslim pilgrim setting off for the Hajj in 1885 can expect to go through…

Sumit Kumar: I’ve been saving for Mecca for years. My journey began near Hyderabad and I traveled by rail and bullock carts to the big city – …Bombay.

I went straight to a Haj broker. These men are swindlers, but I was careful… I bought a ticket. There was a departure date, but these ships don’t leave until they are full. I stayed at a friend’s chawl near Thakurdwar and every day, I went to the port to check on the ship.

Before departure, I went to the medical camp, where some men inspected me for disease. They doused my bag in steam and gave me papers. I also got a pilgrim passport.

On departure day, the port was madness. Policemen were hitting people with their batons. The pilgrims swelled onboard, not looking back.

We were all dreaming of Mecca. The crowd carried me, up to the ship, down a hatchway. I found a small space inside the ship.

The steamship set off for Kamaran Island, a barren land in the Red Sea – hell on Earth. A quarantine station. I hear the Ottomans run it. I was exhausted from my month-long journey, from the stench of people and excrement, the lack of food. I was shoved into a dinghy and rowed to the island. Attendants scrubbed me, and steamed my luggage. They pushed me into a hut where I have to stay with 60 other pilgrims for 10 days. The heat is suffocating. I have 11 square feet to myself. I have to pay for this confinement, for the over-priced food . I’m here. I’m afraid. If cholera occurs in this group, we will be trapped in Kamaran for weeks. The disease will run through this crowd.

I may even miss Mecca.

***

Gayathri: Kamaran has a terrible reputation. One Indian who does this pilgrimage wrote this poem–

Sumit Kumar: Mid Jeddah and Aden way

The quarantine at Kamarn lay.

The Hajis of the Indian land

Are first tried on this sand;

If one can save his life here,

In going to Haj he has no fear.

Who does not die in 10 days,

Good luck he has in all his ways.

O! for the sake of quarantine,

Thy (god’s) prisoners all of us have been.

Chapter 5 – Borders

Gayathri: So maybe by now, you’re wondering… why bother our heads about some ancient outbreak today, when our house is burning right now? … Well, here’s why.

Mary-Rose: Take airports. It’s amazing to think that for much of human history, people mostly travelled as they pleased. But during cholera, Europeans begin stringent and permanent border controls. Pilgrim passports. bills of health. Vaccination certificates. Sound familiar? We know versions of them today as passports, visas. These documents restrict the movement of people from the developing world, even in non-pandemic years. And very often, the reason given for the restriction is disease.

Gayathri: Here’s an example. When Alison Bashford, a historian of medicine at the University of New South Wales, hosted a conference in Sydney, she found that people from developing nations kept dropping out. As if to prove a point, it was a conference on medicine and borders…

Alison Bashford: I can remember first of all, it was someone from Afghanistan, then it was someone from Pakistan. And then it was someone from Chile, if I remember correctly. And then there started to be a global South pattern of people who were pulling out of my global conference called medicine at the border. And I thought, what is going on here? Is this something as mundane as funding, in which case I can try and fix that

Gayathri: It turned out that people from some parts of the world had to get medical tests done, prove they aren’t diseased… the scholar from Afghanistan, for example, he had to get a TB test… and that was a hassle …

Alison: The demographic of my conference ended up being almost all Europeans and North Americans.

Mary-Rose: And here’s another example of how our lives today are still defined by the cholera pandemic… remember those racially-charged International Sanitary Conferences? Those recommendations are still with us! They led to something called the International Health Regulations, created by the World Health Organization in 1969.… These are legally binding rules that dictate how the 196 member nations of the WHO should act when there’s a global health emergency.

Gayathri: Like Covid19?

Mary-Rose: Exactly. And in 2005, the WHO rewrote the regulations, to make surveillance an even more central part of public health, says Martin French..he’s a sociologist and surveillance expert at Concordia University in Montreal.

Martin French: many states, especially in so-called low resource areas, would be better served by investing in more fundamental components of public health than they would by spending money on trying to create surveillance systems.

Mary-Rose: He says this focus on surveillance can be seen…

Martin: as a way to contain infectious disease in poor areas, giving wealthy states the capacity to quickly act to protect themselves by closing borders and so on. We can trace this critique, and we can trace in some sense the containment logics of the international health regulations and of the global public health system to multiple origin points, but one of these origin points would certainly be European colonialism.

Mary-Rose: So, the events of the 19th century are the building blocks of our response to COVID19, to Ebola before this, to Zika, SARS….

Gayathri: And we’ve largely forgotten that our current international legal response to pandemics is built on problematic colonial assumptions about race that discriminates against the poor and disenfranchised.

Mary-Rose: And while we can’t tell you whether there’s a better system to be devised… that’s above our paygrade, as they say, we’ve seen some troubling origins of our response.

Gayathri: We are well into a world of COVID19 vaccine certificates and negative Covid tests to get on planes, to attend music concerts… but what will happen now that the world is segregating into the vaccinated and the un-vaccinated?

Mary-Rose: the rich and the poor

Gayathri: and mostly white, and mostly people of colour

Mary-Rose: As for cholera, the main character of this story — it’s still around. It cropped up in Yemen. Mozambique, Zimbabwe in 2018, Niger, Iraq, Pakistan, in Haiti: …in pockets with unclean water, weak infrastructure and poor governance.

Credits

Gayathri: Thanks for listening. This was Episode 4 – Pandemics and Borders. I’m Gayathri Vaidyanathan.

Mary-Rose: I’m Mary Rose Abraham… there’s another part to this story — in 1896, two Indian freedom fighters embark on a plot to retaliate against border control measures. Listen to this bonus episode, called “Assassination”, on our patreon — patreon.com/scrollsandleaves.

Gayathri: Next time on Scrolls & Leaves, you’ll hear about the story of an indentured labourer from India who leaves to a British Colony in search of a new life.

Mary-Rose: Our sound designer is…

Nikhil Nagaraj: Nikhil Nagaraj.

Mary-Rose: The storyteller is… Sumit Kumar.

Mary-Rose: You were listening to Scrolls and Leaves, in collaboration with the Archives at the National Centre for Biological Sciences.

Gayathri: Our thanks to David Arnold, Alison Bashford, Pratik Chakrabarti, Martin French …

Mary-Rose: … Sanjeev Jain, Projit Mukherji, and Tarangini Sriraman.

Gayathri: Thank you to our episode sponsors – IndiaBioscience and DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance.

Mary-Rose: Visit scrollsandleaves.com for episode notes, extended interviews with our experts, and to discuss. We’re listening. And of course, please subscribe on your favorite podcast platform and spread the word!